Protecting a design work

A work of industrial design (design) is protected (mostly) by registration with the Patent and Trade Mark Office (both nationally and internationally), provided it meets the requirements of novelty, individual character and lawfulness, prescribed by Articles 32, 33 and 34 of the Industrial Property Law (Legislative Decree No. 30/2005) and ascertained by the Patent and Trade Mark Office to authorise its registration.

Registered Designs

The first requirement (novelty), consists in the absence of disclosure of the industrial design before the application for registration of the design was filed, or the claiming of priority, prior to the date of the application.

However, the IP Law provides for some exceptions to novelty if the work has been pre-disclosed in certain contexts (e.g., at an exhibition, official or officially recognised) or in a specific time frame (in the 12 months prior to the date of registration), or has been disclosed to a third party under explicit or implicit confidentiality obligations.

A product, on the other hand, has individual character when the overall impression created by the work in the informed user differs from the overall impression created in that user by any design that has been disclosed prior to the date of filing of the application.

Finally, a design is lawful if it is not contrary to public order or morality.

Designs are considered identical when their features differ only in irrelevant details.

The protection of unregistered designs

However, not all designs are registered, but there is no risk of the author of a design work being left without legal protection.

In this case, in fact, the Law on Copyright (Law No. 633 of 20.04.1941, or ‘L.d.A.’), in Article 44, provides for 70 (seventy) years of protection in favour of the author of the industrial design work, provided that the latter has, in itself, creative character and artistic value, pursuant to Article 2, no. 10.

The first requirement (creativity) is the necessary basis for copyright protection and requires that the work does not consist of a mere copy of another, but is, in fact, created from scratch by the author.

Artistic value, on the other hand, relates to aesthetic ‘worthiness’ and – according to case law pronounced over time – this requirement is assessed through collective recognition, which can be found in exhibitions and shows, as well as reviews, ratings and awards provided by art experts.

The Requirements of Creativity and Artistic Value

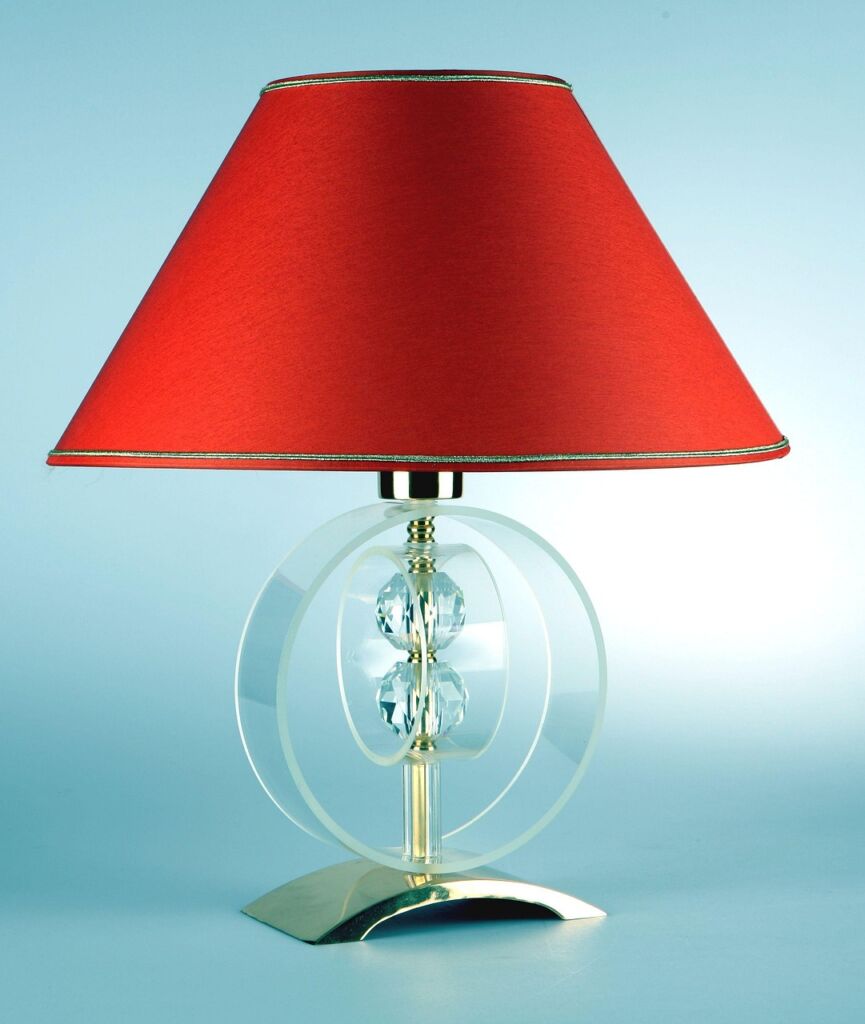

The Court of Cassation recently ruled precisely on the protectability of an unregistered design work (in this case, a lamp conceived and created to be included in the setting up of an exhibition), specifying the characteristics of the requirements of creativity and artistic value that the work must possess (Civil Cassation, Section I, Order No. 11413 of 29 April 2024)

The creative character

First of all, the Supreme Court, conforming to both national and European case law, specified that the requirement of creativity consists, not in the idea underlying it, but ‘in the form of its expression, i.e. its subjectivity, assuming that the work reflects the author’s personality, manifesting his free and creative choices (conforming pronouncements: Civil cassation, sentence no. 10300/2000; Cass. civ., judgment no. 8433/2020; Court of Justice of the EU, judgment of 12.09.2019, case C-683/17)’.

The artistic value

Moreover, the judges of legitimacy, in the aforementioned order, reiterated that the artistic value of the work must be detected on the basis of objective parameters – which do not necessarily all have to be present at the same time – such as:

- the recognition, by cultural and institutional circles, of the artistic and aesthetic qualities

- exposure in exhibitions or museums;

- publication in specialised magazines;

- the awarding of prizes;

- the acquisition of a market value so high as to transcend that linked solely to its functionality;

- creation by a well-known artist.

These parameters, moreover, ‘must be recognisable, even through recourse to circumstantial criteria’ (Conforming pronouncements: Cass. no. 33199/2023; Cass. no. 23292/2015).

The Lamp

The case that was the subject of the ordinance concerned a dispute brought by the daughter and heir of a well-known architect, author of a specific lamp, against another architect, author and designer of the ‘1954’ lamp, because of an alleged plagiarism of the first work, created by her father.

The order in question, applying the above-mentioned principles of law, ruled that the community and, in particular, cultural circles, perceive as a work of design not the lamp in itself, but “its scenographic function, and that the iconic importance of the same is not to be attributed to the illuminating body in and of itself, but to its use as an instrument of the exhibition space, reduced to a dark container, of which only the horizontal dimension remains, broken up by the articulated sequences of large platforms”.

The Court of Cassation, therefore, ruled that “copyright protection was therefore to be limited to the installation as a whole and not to the single illuminating instrument for which no subsequent and further specific recognition had emerged”.